Despite its critical acclaim, I Am Legend did little to improve the somewhat dire financial straits of its author’s growing family, which his eldest child, Bettina (fictionalized in “Little Girl Lost”), dramatically described in The Richard Matheson Companion. Writing during the morning while cutting out airplane parts for Douglas Aircraft in Santa Monica by night, he resolved that if his next effort did not bear greater fruit, he would abandon his literary aspirations and work for his older brother, Robert. So Matheson returned to his boyhood home of New York to rent a house in Sound Beach on Long Island, whose cellar he used as the primary setting for his fourth novel.

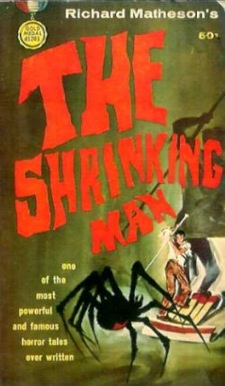

Said novel, The Shrinking Man, changed the course of literary and cinematic history, because Matheson made the sale of the film rights to Universal, then known as Universal-International, contingent on his being allowed to write the screenplay. That sale, bolstered by the film’s box-office success, enabled him to move back to California permanently and devote himself to a full-time writing career. Even before the book’s publication as a Gold Medal paperback original in 1956, Matheson was in Hollywood, hard at work on the script, although in a letter to William H. Peden, his college writing professor, he expressed characteristic frustration at repeating himself.

Like I Am Legend, with its plague spread by dust storms resulting from an apparent nuclear war, the novel nicely captured the Cold War anxieties of its day, since one cause of the protagonist’s diminution was the then-ubiquitous bugbear of radioactivity. It also tapped into timeless social, sexual, and philosophical themes, with Scott Carey’s literally diminished role as husband, father (excised from the film), and human being. U-I insisted that the film eschew the novel’s elegantly intertwined flashback structure, prefiguring the likes of The Godfather Part II (1974)—in which, I might add, Matheson did not have an uncredited role as a senator, contrary to Internet rumors.

U-I assigned the film to staff producer Albert Zugsmith, who added the superfluous adjective to Matheson’s title, and house SF expert Jack Arnold, who had directed It Came from Outer Space (1953) and Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954). Their fifth and final collaboration, MGM’s High School Confidential! (1958), epitomized Zugsmith’s subsequent career in exploitation films, characterized by sensational subject matter and eclectic casts, usually headed by Mamie Van Doren. Arnold’s filmography, conversely, is such that it is difficult to single out one masterpiece, but The Incredible Shrinking Man—which won a 1958 Hugo Award as Outstanding Movie—is a contender.

Alone on deck when his brother’s boat passes through a glowing mist, Scott Carey (Grant Williams) begins to shrink six months later, and the doctors deduce that the radioactive residue interacted with some insecticide to produce unprecedented results. His travails growing in inverse proportion to his stature, Scott learns that his brother and boss, Charlie (Paul Langton), can no longer keep him on the payroll, and finds his marriage to Louise (Randy Stuart) disintegrating. After an affair with carnival midget Clarice Bruce (April Kent) offers temporary solace, Scott is reduced to living in a dollhouse when he is trapped in the cellar by the family’s cat, Butch, which Louise believes has devoured him.

Scott’s odyssey through the cellar and beyond is a true tour de force, an engrossing story enhanced by effects that in many cases remain impressive even now, combining oversized sets and props with Clifford Stine’s special photography. Subsisting on mousetrap cheese and stale bits of cake left by Louise, Scott is understandably despondent, but somehow finds the will to go on and even dominate his brave new world, confronting the spider that towers over his tiny form and impaling it with a pin in a tense climax. Using techniques they had pioneered in Tarantula (1955), Arnold and Stine made his fight with this fearsome arachnid adversary one of the most memorable sequences in SF cinema.

Convinced that his steady rate of shrinkage will eventually cause him to dwindle out of existence, Scott is astonished when he becomes small enough to leave the cellar through a screen and goes on shrinking, presumably to sub-atomic size. Sadly, Arnold tried to take credit for this unusual (not to mention uncommercial, in the studio’s eyes) ending himself, conveniently overlooking the fact that Scott’s closing narration echoes the novel almost verbatim. Regardless, Matheson’s metaphysical conclusion distinguished the film from the run of giant-monster and alien-invasion potboilers in the 1950s, and its success helped ensure classic status, as well as several follow-ups in various forms.

Due to budgetary concerns, the remake that John Landis had developed for Saturday Night Live star Chevy Chase devolved upon first-time director Joel Schumacher and Laugh-In veteran Lily Tomlin as The Incredible Shrinking Woman (1981). Satirizing consumerism, advertising, corporate greed, and environmentalism, it was widely criticized for adopting the perspective of a detached observer rather than that of the title character. Matheson’s agent recently informed me that a second comedic version, announced years ago as a possible vehicle for Eddie Murphy, and Countdown, the feature-film adaptation of his story (and Twilight Zone script) “Death Ship,” are no longer in development.

Interestingly, a distaff viewpoint was central to not only the remake, but also The Fantastic Little Girl, Matheson’s unfilmed sequel (which appears in his Gauntlet collection Unrealized Dreams). Matheson’s “girl” is Louise, who was down below getting Scott a beer when Charlie’s boat passed through the mist, but experiences a delayed reaction that lets her share in his microscopic backyard adventures before both fortuitously return to normal size. “The Diary of Louise Carey,” a Shrinking Man variation written by Thomas F. Monteleone for Christopher Conlon’s tribute anthology He Is Legend, portrays Louise as a dissatisfied wife who resents Scott and supplants him with his brother.

Matthew R. Bradley is the author of Richard Matheson on Screen, due out any minute from McFarland, and the co-editor—with Stanley Wiater and Paul Stuve—of The Richard Matheson Companion (Gauntlet, 2008), revised and updated as The Twilight and Other Zones: The Dark Worlds of Richard Matheson (Citadel, 2009). Check out his blog, Bradley on Film.